Jessica de Abreu is an anthropologist and activist, co-founder of the Black Archives, a project based in Amsterdam that documents the history of Black emancipation in the Netherlands, its former colonial territories, and elsewhere. She kindly accepted to answer our question on her involvement in the movement criticising the racist and colonial imagery of the Sinterklaas festivities, a Dutch tradition which takes place in the Netherlands and in Potsdam.

Mnyaka Sururu Mboro was born in 1951 and lives in Berlin. He is a Tanzanian activist, co-founder of the NGO Berlin Postkolonial. He has been actively campaigning for the acknowledgment of German colonialism in the public sphere since the 1980s. He leads guided tours through the so-called “African Quarter” in Berlin and is board member of the NGO Decolonize Berlin. In this short piece, he tells us about his experience with colonial perspectives on history and gives us his recommendation for the future of the installation with the alleged “peak of Kilimanjaro” in the New Palace in Potsdam.

→ read more

Farai von Pentz:

One day, I cycled from Berlin to Potsdam, just to have a look at the campus. I probably took a detour when I rode through the Sanssouci Park and found myself standing in this so-called M*rotary. So I saw those statues even before I enrolled at the university. I could not not notice them. As a Black person, these things immediately catch your attention. When you ride or walk through such a park, which appears so dreamlike when you don’t know anything about its history, you admire the beautiful buildings and statues. And then suddenly, these statues made out of black marble stood in front of me. I stopped and had to look more closely. I was puzzled. My feeling was: what is this doing here? How do these statues fit in the park?

Angelo Camufingo:

The Sanssouci Park, and by extension the M*rotary, were integrate part of my life as a pupil. When we as a class or group stood in front of it or passed it, I felt that it was strangely addressed to myself or my family, even in an offensive manner. I just knew that the people who were depicted there were not looked at or depicted with the same freedom or value as other characters in the park. I knew it wasn’t about the beauty, strength and aesthetics of Black people. From my perspective, the rotary and the busts embody enslavement, racism, colonialism, and the complete degradation of people whose exploitation has been responsible for the wealth and power of the West and a white majority society.

Oduor Obura is a Kenyan writer and scholar. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Potsdam. He has written about the construction of African childhood and the colonial history of museums. For Postcolonial Potsdam, he gives us his perspective on the four black figures in the Park Sanssouci and the alleged presence of the “peak of Kilimanjaro” in the New Palace.

Oduor Obura is a Kenyan writer and scholar. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Potsdam. He has written about the construction of African childhood and the colonial history of museums. For Postcolonial Potsdam, he gives us his perspective on the four black figures in the Park Sanssouci and the alleged presence of the “peak of Kilimanjaro” in the New Palace.

An Interview with SchwarzRund

An Interview with SchwarzRund

Who are you?

I am SchwarzRund. By now, it has become my official pen name. First it was the name of my blog, but now I publish everything, artistic or academic, under that name.

I am a Black Dominican in Germany with both passports and I work in various fields. Storytelling and poetry/performance texts are the heart of my work. But painting, writing and online ranting are very important to me as well – for my activism and for me personally…

Our initiative Postcolonial Potsdam was born in 2014. Back then, some of our members were part of a team organising a conference called “Postcolonial justice”. It took place at the University of Potsdam, 200m away from two statues of Africans. Scholars and authors came from far to address inequalities and discrimination resulting from colonial contexts, past and present. Some had even traveled from Australia to Potsdam. While we learnt about the effects of colonial rule all over the world, we also asked ourselves: are there places here in Potsdam that are traces of colonialism?

Our initiative Postcolonial Potsdam was born in 2014. Back then, some of our members were part of a team organising a conference called “Postcolonial justice”. It took place at the University of Potsdam, 200m away from two statues of Africans. Scholars and authors came from far to address inequalities and discrimination resulting from colonial contexts, past and present. Some had even traveled from Australia to Potsdam. While we learnt about the effects of colonial rule all over the world, we also asked ourselves: are there places here in Potsdam that are traces of colonialism?

In front of the New Palace, facing the Park Sanssouci, there are two statues of Africans holding lamp-posts. These were one of the first discoveries of our team. We asked ourselves: what is their purpose? Did the sculptor use any African as a model for these statues? If yes, did this person live in Potsdam? We were eager to find a hidden story behind those quiet statues… → read more

The New Palace is the last building built in the Sanssouci Park. Its construction started in 1769. It’s considered to be the last Prussian baroque palace, built during the reign of Friedrich the Great. It was built as a symbol of his power. The King used it as a reception venue for important dignitaries. A century later, the German Kaiser Wilhelm II renovated the New Palace and made it his favorite residence until 1918.

Inside, there is a massive reception room called the Grotto Hall. Look at the picture of the room: hundreds of colorful stones and shells decorate the walls and ceiling. Among those rocks, one is particularly interesting to us. Sitting on a miniature mountain, a lava rock is described as being the peak of the Kilimanjaro… → read more

The New Palace is the last building built in the Sanssouci Park. Its construction started in 1769. It’s considered to be the last Prussian baroque palace, built during the reign of Friedrich the Great. It was built as a symbol of his power. The King used it as a reception venue for important dignitaries. A century later, the German Kaiser Wilhelm II renovated the New Palace and made it his favorite residence until 1918.

Inside, there is a massive reception room called the Grotto Hall. Look at the picture of the room: hundreds of colorful stones and shells decorate the walls and ceiling. Among those rocks, one is particularly interesting to us. Sitting on a miniature mountain, a lava rock is described as being the peak of the Kilimanjaro… → read more

Between 1901 and 1919, Chinese astronomical instruments decorated the patio in front of the Orangerie in Potsdam. Germany had to give them back to China as part of the reparations for the First World War. These instruments had been looted by the German military during a period of German colonial occupation in China. This conflict is known in English as the Boxer War or 義和團運動. → read more

In Weinbergstraße 9 in Potsdam stands a house with yellow bricks. It was built in 1843 by the architect Ludwig Persius for a man called Fung Ahok. Ahok was a renowned Potsdamer at the time, one of the first Chinese people to live in Prussia. The history of this man and his partner Fung Asseng is related to the beginning of sinology in Germany, but also to colonial trade and racial anthropology.

This is an article by Fabienne Imlinger

Here, in front of the Sanssouci Palace, we would like to take you to Haiti in the Caribbean, where another Sans-Souci palace was built. It is 1813 in Haiti. In the last years, King Henry I, a fan of architecture, has personally supervised the construction. But his Sans-Souci is more than just a lavish residence for the King. It is a monument for the nation of Haiti, a nation who has just released herself from the shackles of slavery and colonialism. Ten years have passed since the victory over the French and their colonial rule. The independence of Haiti was proclaimed symbolically on 1st January 1804. But since then, none of the European powers have officially recognized the young state… → read more You stand at the centre of the so-called M*word-rotary. If you haven’t yet learned about its meaning in the architecture of the park, please read our contribution on the Obelisk and the Axis of Power. Here, we want to talk about the relevance of these statues today.

The name commonly used for this rotary includes the M*word, a term that has contributed to the history of racism in Germany. This name has been the subject of controversy. In 2014, a public debate took place on whether the city or the Foundation Prussian Palaces and Gardens should rename this rotary. Local politicians and organisations asked whether its offiicial name is appropriate today.

Because of the underlying layers of racist history in this composition, we have called for renaming this rotary in the books. We also wish for some kind of context for these statues. An information board should inform visitors on the meaning of this rotary in the park. It should also tell about colonialism and racism in Prussian history. → read more

You stand at the centre of the so-called M*word-rotary. If you haven’t yet learned about its meaning in the architecture of the park, please read our contribution on the Obelisk and the Axis of Power. Here, we want to talk about the relevance of these statues today.

The name commonly used for this rotary includes the M*word, a term that has contributed to the history of racism in Germany. This name has been the subject of controversy. In 2014, a public debate took place on whether the city or the Foundation Prussian Palaces and Gardens should rename this rotary. Local politicians and organisations asked whether its offiicial name is appropriate today.

Because of the underlying layers of racist history in this composition, we have called for renaming this rotary in the books. We also wish for some kind of context for these statues. An information board should inform visitors on the meaning of this rotary in the park. It should also tell about colonialism and racism in Prussian history. → read more

This is a guest contribution by Lillian Dam Bracia.

This is a guest contribution by Lillian Dam Bracia.

Located in the heart of the city, the ‘Dutch Quarter’ is no bigger than four house blocks. This picturesque neighborhood is home to the largest closed Dutch-style buildings outside the Netherlands. The facades of terraced houses consist entirely of red Dutch brick with white joints. It was built between 1733 and 1742 by Dutch architect, Jan Boumann, under the rule of Prussian King Frederick William I and his son, Frederick II.

Prussia was proud of its friendship with its Dutch counterpart. However, what is dismissed is another and rather dark history of this time. One shouldn’t forget that when the Dutch quarter was being constructed, the Netherlands had built a powerful colonial empire and were participating in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Although from a first impression one would not expect from these cute houses to retain secrets, the troubling fact is they do. They hold secrets tied to slavery, colonialism and racism… → read more

The rotary of the Oranges is one the largest squares in the Sanssouci Park. The busts represent several Dutch princes and princesses from the House of Orange. Over the years, Dutch and Prussian aristocrats arranged several marriages to cement relations of kinship between them. The large size of this rotary can be interpreted as a sign of respect to those esteemed friends and relatives of Prussia. In the 18th century, Prussia admired the Netherlands for their architecture, their empire and their global trade relations. Taking the rotary of the Oranges as our point of departure, we want to focus on the friendship between the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm of Brandenburg and the Dutch. This relationship explains the colonial aspirations of Friedrich Wilhelm who ultimately participated in the transatlantic slave trade and erected a colony on the African coast… → read more

…This house was built in 1754. It was commissioned by the Prussian King Friedrich II, also called Friedrich the Great. It is now considered as one of the most important monuments of the Chinoiserie, a European artistic fashion of the 18th century. European aristocracy had indeed an admiration for China. They imagined a faraway land ruled by reason and a model for taste, style and culture. But few Europeans had actually visited China or even met Chinese people. Born out of wonder and curiosity for the unknown, these assumptions were repeated in European art, architecture and literature. Friedrich II himself was a fervent admirer of the Chinoiserie fashion. He even wrote several letters and philosophical essays under a Chinese pen name. In building the teahouse, he would erect a temple for his fantasy of an idyllic China. However, nothing here has anything to do with actual Chinese art. It only conveys the imagination of its maker… → read more

This is a guest contribution by Naomie Gramlich und Lydia Kray.

In this text for our series on Potsdam’s botanical garden and its colonial entanglements (first part here), we deal with two issues: the colonial role of European scientists in practices of naming and the restitution of botanical specimen.

This is a guest contribution by Naomie Gramlich and Lydia Kray

Understanding botanical gardens as colonial sites seems particularly difficult: their plant inhabitants present themselves as too innocent, too splendid and too lively to be associated with colonial violence, white appropriation and hegemonic systems of knowledge production. To imagine which countries the plants come from and at what time they came to Europe fundamentally changes the perspective of visitors to these institutions. To begin to trace the hidden colonial layers, we met the curator of the Potsdam botanical garden, Dr. Michael Burkart. He provided us with insights into his still unwritten work about the plants’ colonial histories. This text takes this conversation as a starting point and then asks questions about the origins, movements and possible return of the plants. We want to use the current debate on the restitution of African cultural artifacts as an opportunity to raise questions about the colonial heritage of botanical gardens as well… → read more

As we read about the painting of Achmed hanging in Glienicke Palace in SchwarzRund’s novel Biskaya, we decided to go and see it. In July 2018, we then went on a Postcolonial Potsdam team excursion to the Palace.

The Glienicke Palace is located in the South-West of Berlin, right by the city’s boundary to Potsdam. When we arrived, we learned that we could only enter the Palace with a tour guide and not on our own. All the better, we thought, because it is always interesting to learn about the institution’s own narrative of the historical events it presents. The Glienicke Palace belonged to Prince Carl of Prussia (1801-1883), a huge fan of Italy who wanted to recreate an impression of the Italian landscape and architecture right there…

→ read more

As we read about the painting of Achmed hanging in Glienicke Palace in SchwarzRund’s novel Biskaya, we decided to go and see it. In July 2018, we then went on a Postcolonial Potsdam team excursion to the Palace.

The Glienicke Palace is located in the South-West of Berlin, right by the city’s boundary to Potsdam. When we arrived, we learned that we could only enter the Palace with a tour guide and not on our own. All the better, we thought, because it is always interesting to learn about the institution’s own narrative of the historical events it presents. The Glienicke Palace belonged to Prince Carl of Prussia (1801-1883), a huge fan of Italy who wanted to recreate an impression of the Italian landscape and architecture right there…

→ read more

Next to the Chinese Tea House, you can find the only authentically Asian object in the Sanssouci park: a rather insconpicuous incense urn from Siam, what is today Thailand. This urn was offered as a present to the German Emperor Wilhelm II in 1897 by Siam’s emperor Chulalongkorn. → read more

This is a guest contribution by Stefan Theilig

The Garrison church is a landmark in Potsdam. It has a long history: it burnt down during the Second World War, then the socialist party destroyed it, and in 2018, the city started rebuilding it. But it is interesting to us because it is in this church that African and Ottoman members of the Prussian army were forcibly baptized in the 18th century.

This is a byline article by Stephan Theilig.

This is the military orphanage, where a school for military music was established in the 18th century. The history of Prussian military music tells us quite a lot about the conditons of African servants at court.

Before the existence of a Prussian standing army, an important part of mercenary troops was composed of musicians. There were drummers and pipers in the infantry. Trumpet and timpani players were part of higher arms of the service, such as the cavalry. Their role was not like that of a marching band today. They were used to send signals to the battling troops. Friedrich Wilhelm the Great Elector invested in this military corps. Throughout the years, it became integrate part of Brandenburg-Prussia’s standing army. → read more

On 2nd September 2020, the Foundation Prussian Palaces and Gardens announced that it would rename the so-called “M-word-rotary” into “First rotary”. In a press conference on 14th May 2021, the foundation confirmed this decision and unveiled an information board contextualising this renaming action on site. On 20th August 2020, the district council in Berlin Mitte announced that it agreed to the future renaming of the M-word-street into Anton-Wilhelm-Amo-street. On 15th August 2020, the Hotel “Three M-word” in Augsburg also announced that it would change its name.

On 30th November 2019, the members of the working group Postcolonial Potsdam invited experts on colonial history and postcolonial cultures to present different aspects of Potsdam’s colonial heritage. This gathering aimed to produce content for an upcoming mobile app that would guide its users through Potsdam and make them aware of traces of colonial history in the city, especially the Park Sanssouci. This project, a cooperation with the Research Training Group “Minor Cosmopolitanisms” and supported by Junges Engagement Berlin Brandenburg and Altomayo Coffee, draws on five years of experience with guided tours offered by Postcolonial Potsdam…

On 30th November 2019, the members of the working group Postcolonial Potsdam invited experts on colonial history and postcolonial cultures to present different aspects of Potsdam’s colonial heritage. This gathering aimed to produce content for an upcoming mobile app that would guide its users through Potsdam and make them aware of traces of colonial history in the city, especially the Park Sanssouci. This project, a cooperation with the Research Training Group “Minor Cosmopolitanisms” and supported by Junges Engagement Berlin Brandenburg and Altomayo Coffee, draws on five years of experience with guided tours offered by Postcolonial Potsdam…

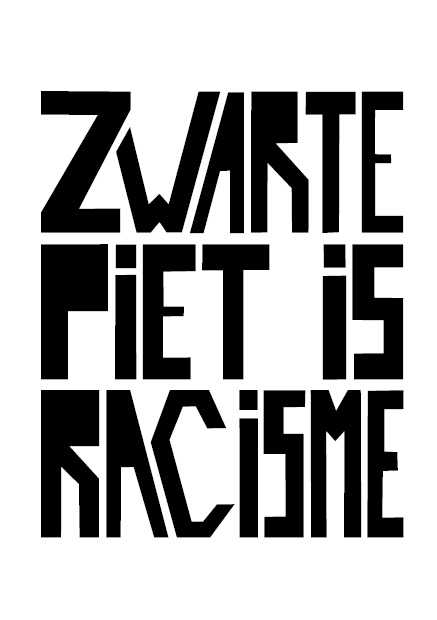

Last weekend, the second weekend of December 2016, Potsdam celebrated once again the arrival of the Dutch Sinterklaas and his companions, the Black Petes… Last year, the City of Potsdam realized that they could not continue to financially support the organization Förderverein zur Pflege niederländischer Kultur in Potsdam, which coordinates the Sinterklaas festivities, if the yearly event continued to include racist elements. To convince the local politicians and sponsors, it took several long meetings with representatives from organizations such as Afrika Rat, ISD, PAWLO, Opfer Perspektive and ourselves, a panel discussions and an open letter by several professors of the University of Potsdam. As a consequence, there was no Sinterklaas and no Black Petes in Potsdam last year, the festivities were only celebrated with a Christmas market. This year, however, the Förderverein announced they would be able to host the Sinterklaasfest again since they found Dutch partners who agreed to stage Sinterklaas and the Petes’ arrival without blackface…

→ read more

Witty interventions on the peak of Kilimanjaro at the Grassi Museum Leipzig

On 4th March 2022, the exhibition “Moving Mountains” (“Berge versetzen“) opened at the Grassi Museum in Leipzig. As a collaboration between the artistic collective PARA, Rehema Chachage and Valerie Asiimwe Amani, this exhibition tackles the story of the displacement of the peak of mountain Kilimanjaro and Hans Meyer’s legacy, a story we also tell in our tours. The exhibiton brings fresh perspectives on German colonialism and invite the visitors to revisit this history with humour, creativity and self-reflexivity.

Here’s our review: → read more

W: Ich bin die hier-sprichst-du Wand, der du nach dem Besuch der Ausstellung begegnest. Hier sprichst du…

B1: Addet mich auf Snapchat

B2: DADADADadadadDADADdadada

W: Was ist das Fremde?

B3: Good question which would have been interesting (if not necessary) to explore in that exhibition

Until 7th November 2016, the Berlinische Galerie featured the special exhibition Dada Afrika – Dialog mit dem Fremden, associating early 20th century artists of the Dada movement with a multitude of non-European artistic and cultural objects that provided artistic inspiration to the Dadaists. In an adjacent room to this exhibition, the Berlinische Galerie has opened up a space for creative engagement with Dada, as well as to encourage visitors to participate in the so-called ‘dialogue’ by expressing their thoughts on the exhibition with post-its on the “Hier-sprichst-du” wall. At the time of my visit, around 60% of the messages could be summed up in “DaDa”, dAdA” or “DAda ist cOOl”. The evident aim of the wall was however to reflect on concepts that, though not addressed by the exhibition, yet remained central to the exhibition of African, Oceanian or North American indigenous artworks, such as the “other” or German colonialism. The gap between the purpose of the wall and the response of visitors is telling… → read more

In May 2016, the Sophiensaele in Berlin hosted the lecture performance Schädel X (Skull X), a production by the theatre company Flinn Works. Thanks to an impressive research effort to pursue a historical revision of German colonialism and a report by Gerhard Ziegenfuß, the performance reminded its audience of a German collecting mania: at the core of the matter, human remains of formerly colonized peoples who have been snatched and brought to Europe. The lecture performance deals with the genocide of the Herero and Nama in former German South-West Africa as well as with colonial violence German East Africa, today’s Tanzania… → read more

In May 2016, the Sophiensaele in Berlin hosted the lecture performance Schädel X (Skull X), a production by the theatre company Flinn Works. Thanks to an impressive research effort to pursue a historical revision of German colonialism and a report by Gerhard Ziegenfuß, the performance reminded its audience of a German collecting mania: at the core of the matter, human remains of formerly colonized peoples who have been snatched and brought to Europe. The lecture performance deals with the genocide of the Herero and Nama in former German South-West Africa as well as with colonial violence German East Africa, today’s Tanzania… → read more

In December 2015, T-Werk in Potsdam hosted a panel discussion which set out to provide background information on the connection between racism and the German and Dutch use of the tradition of blackface. This event was a reaction to the highly emotional debates in Potsdam around the well-loved Sinterklaas celebration and especially the traditional performance of Zwarte Piet. Fortunately, the city of Potsdam has decided to deny any financial support of the event in case it continues to include the racist practice of blackfacing the Zwarte Pieten characters. Potsdam has thus declared itself against a perpetuation of colonial traditions… → read more

In December 2015, T-Werk in Potsdam hosted a panel discussion which set out to provide background information on the connection between racism and the German and Dutch use of the tradition of blackface. This event was a reaction to the highly emotional debates in Potsdam around the well-loved Sinterklaas celebration and especially the traditional performance of Zwarte Piet. Fortunately, the city of Potsdam has decided to deny any financial support of the event in case it continues to include the racist practice of blackfacing the Zwarte Pieten characters. Potsdam has thus declared itself against a perpetuation of colonial traditions… → read more