Grinding the colonial house

with a jackhammer

Witty interventions on the peak of Kilimanjaro at the Grassi Museum Leipzig

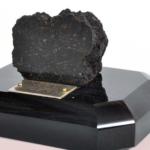

In 2008, the Leibniz Institute for Geography in Leipzig celebrated Hans Meyer’s 150th birthday with an exhibition called “Meyer’s Universe”. In the catalogue published for this event, different authors revisited his famous 1889 expedition to the Kibo, the peak of the Kilimanjaro, publishing photos he had taken along the way, reproducing Meyer’s romantic (and colonial) perception of a giant he ought to tame, a landscape he strove to dompt, a mount he wished to surmount. The catalogue also showed an image of a piece of rock the geographer had taken from the peak and kept for himself as a paperweight.1 We already told you several years ago that he had given the other half to the German Kaiser Wilhelm II after having shamelessly renamed the summit called Kibo into “Kaiser-Wilhelm-Peak”.

But today, Meyer’s grand imperial vision is crumbling down.

The first crack came on 8 December 1961, when “Kaiser-Wilhelm-Peak” was officially renamed “Uhuru Peak” by newly independent Tanzania, a decolonial gesture that foregrounded freedom from colonial rule rather than colonial appropriation.

The second of these rocky issues in Meyer’s problematic legacy are the Benin Bronzes. Meyer indeed acquired several of these masterpieces in the wake of the brutal British expedition against the Oba in 1897 and offered some of these spoiled artworks to the Berlin and Leipzig ethnographic museums at the time.2 As of this year, these will no longer be exhibited there; they are on their way to Nigeria as part of a global movement for restitution of art and belongings looted during the colonial era.

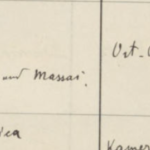

The third is that Europe is currently biting the bullet to the grim presence of thousands of remains of Africans in its anthropological collections. Like many of his contemporaries, Meyer had stolen human remains of Chaga and Masai people and sent them to the Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde in 1899.3 These ancestors are now subject to provenance research and awaiting repatriation, together with other ancestral remains from East Africa.

An additional blow to Meyer’s pride was struck when the Foundation Prussian Palaces and Gardens found out that the piece of rock he had handed over to the Kaiser had been lost in the second half of the 20th century and replaced by a fake one from Meyer’s mineral collection. This means that only one of Meyer’s two pieces of the peak of Kilimanjaro remains intact: his paperweight. Since 2020, Austrian antiquarian Kainbacher has put Meyer’s literary estate, his photographs and this authentic piece of rock for sale… for at least €55,000. They would be ready to sell the rock alone for a minimum of €35,000 after tax.4

The final blow came on 3 March 2022 with the opening of a new exhibition at the Grassi Museum in Leipzig. In a collaboration between the museum, the artist’s collective PARA and Tanzanian artists Valerie Asiimwe Amani and Rehema Chachage, Meyer’s colonial project hits rock bottom. These protagonists and their tools – a jackhammer, a safe, and a pair of dissecting scissors – bring fresh and radical perspectives on German colonialism and invite their audiences to revisit this history with humour, creativity and self-reflexivity.

A plinth central to the museum's history is being dismantled into hundreds of replicas of the peak of Kilimanjaro (Photo: Y. LeGall)

A jackhammer

If Meyer’s minuscule paperweight can be sold for €35,000 while some of the inhabitants of the Kilimanjaro region do not have access to running water and electricity, you will agree that there is something wrong in this world. At the same time, if this original rock is as precious as the gold extracted from the colonies, why not return it to Tanzania so that it can become a touristic attraction and generate local income?

It is with these questions in mind that PARA developed the exhibition Moving Mountains (Berge versetzen), an intervention that addresses the economic dimension of cultural heritage from the colonial era. To raise the money for matching the price set for the real peak, the artists decided to launch a crowdfunding campaign. Visitors of the exhibition (and anyone with a smartphone) can indeed purchase fake replicas of the rock for 20 bucks, replicas that are crafted every day by the artists in a room dedicated to the production chain in the Grassi Museum.

These replicas, however, do not come from the Kilimanjaro, but from the museum’s building. With the help of a jackhammer, the artists dismantled a plinth on which the bust of the former director of the Leipzig museum, ethnologist Karl Weule used to be exhibited. After the monument to Hermann von Wissmann, another colonial patriarch who profited from German colonialism in East Africa has fallen. In 1906, in the midst of the Majimaji War (1905-1907), Weule was indeed “collecting” masks in the south of today’s Tanzania, a collection earned him laurels among his peers in Germany. It is nevertheless still unclear how he could lay hands on so many Makonde masks. Far from dismantling the master’s house with his own tools, the museum and PARA still ask: what can be the role of architecture in addressing colonial wrongs? How should Germany engage with the numerous colonial and patriarchal landmarks protected under the legal guise of heritage preservation (Denkmalschutz)? This is a question we also asked to the Foundation Prussian Palaces and Gardens when discussing the future of the equestrian statue of slave trader Friedrich Wilhelm. In a row on the fate of those stony figures, PARA and Grassi have decided to rock the boat and side with decolonial fallism and its recycling creativity.

On the right: view of the interior of the safe where the Zugspitze is kept hostage. (Photo: Y. LeGall)

A curious hostage in a safe

Another layer addressed in this exhibition is the colonial appropriation of nature. Meyer felt entitled to give names to mountain peaks; he renamed the second peak of the mountain, the Mawenzi, “Purtscheller’s peak” in honour of his Austrian colleague. The Kaiser, in turn, felt entitled to displace the Kibo from East Africa to Potsdam, keeping it symbolically aloof from its local population, just as African cultural heritage is kept away from Africans, guarded in European museums thanks to border regimes and policies of access.

In a similar gesture, PARA decided to steal the peak of Germany’s highest mountain: the Zugspitze, located in Bavaria. After a successful ascension, they took a piece of rock and brought it to Leipzig where it is kept hostage in a safe. The price for Germany (or Bavaria) to get back its highest summit: €35,000. Should anyone be interested in freeing the Zugspitze, the crowdfunding campaign could thereby swiftly reach its goal and a repatriation of the peak of Kilimanjaro could take place.

But PARA has not yet decided whether they would use the money raised to buy back the real thing. Other options remain open, such as financial support for local NGOs in the Kilimanjaro region. This flexibility mirrors Grassi’s new curatorial practice in being able to react spontaneously to current urgencies and politics. One example: in a glass case dedicated to easter eggs from Eastern Europe, the Ukrainian egg stands surrounded by Russian ones, albeit shown more prominently.5

Dissecting Meyer’s colonial vision with scissors and collage

In this revisit of the story of the peak, something ought not to be forgotten, namely Meyer’s visual appropriation of Tanzanian landscapes. In his photographs and drawings, the Kilimanjaro is bare until he plants the German imperial flag. How can we engage today with this colonial imagery of a terra nullius, a piece of nature ready to be conquered, mounted and drained of its resources? Rehema Chachage and Valeria Asiimwe Amani propose a moving collage, an aesthetics somehow reminiscent of Julie Gough’s Hunting Ground – an installation in which the Trawlwoolway-Tasmanian artist lays bare settler colonial violence hidden in portrayals of Australian landscapes. The two Tanzanian audiovisual artists cut Meyer’s pictures of the mountain and glued them next to each other. They produced an oscillating, vacillating and dizzying view of Meyer’s obsession, a juxtaposition exemplifying his megalomaniac aspirations to glory. In this video projection, they also debunk the myth of a legendary mountain climber, offering a funny dissection of Hans Meyer’s body. The focus is no longer on the man, but on the limbs that carried him to the top of the mountain. This return to the metabolic reminded us that Meyer’s skeletal remains lie not far away from the museum in a Leipzig cemetery, a tombstone occasionally visited by critical tours led by our colleagues of Leipzig Postkolonial.

Last funny thing: Amani is not only the last name of one of the artist. It was also the name of Meyer’s cook, a local man whose contribution to the ascent in 1889 would be too quickly forgotten by German historiography, including the 2008 exhibition. We will not forget him: Muini Amani, carrying Meyer’s stuff, fetching water for him and Purtscheller, setting up the camp, lighting up a fire. Muini Amani, though, too Black to deserve mountains in his name.

Authors: Yann LeGall & Paul Urbanski

Read also: what our colleagues Tanzanian activist Mnyaka Sururu Mboro and Kenyan scholar Oduor Obura have to say on the peak of Kilimanjaro in the New Palace in Potsdam

Excerpt from the acquisiton registries of the Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde between October and December 1899. It stipulates that Meyer send six skulls of Chaga and Massai people as a gift to the museum. ( Inv. 3 Inventarverzeichnis I MV, p. 270)

Photo of Hans Meyer’s paperweight labelled as “Peak of the Kilimanjaro” (Source: Kainbacher’s catalogue XVII)

4: Bastian Sistig and Jonas Fischer from PARA told us that, at first, the antiquarian Kainbacher requested as much as €250,000 for the paperweight alone. He claimed having been approached by interested parties regardless of the high price. After the artists made him aware of the problematic context, the antiquarian was reportedly ready to sell Meyer’s rock for the orginal purchase price: €35,000 net of taxes.