"Jessica de Abreu:

Soot on their faces... I call it blackface-light“

Jessica de Abreu is an anthropologist and activist, co-founder of the Black Archives, a project based in Amsterdam that documents the history of Black emancipation in the Netherlands, its former colonial territories, and elsewhere. She kindly accepted to answer our question on her involvement in the movement criticising the racist and colonial imagery of the Sinterklaas festivities, a Dutch tradition which takes place in the Netherlands and in Potsdam.

Postcolonial Potsdam: Can you please introduce yourself?

Jessica de Abreu: My name is Jessica de Abreu. I was born and raised in Amsterdam. I am an activist and an anthropologist. I have organised demonstrations against Zwarte Piet, this symbol linked to the issue of institutional racism in the Netherlands.

PP: Who is this Zwarte Piet and why is this figure racist?

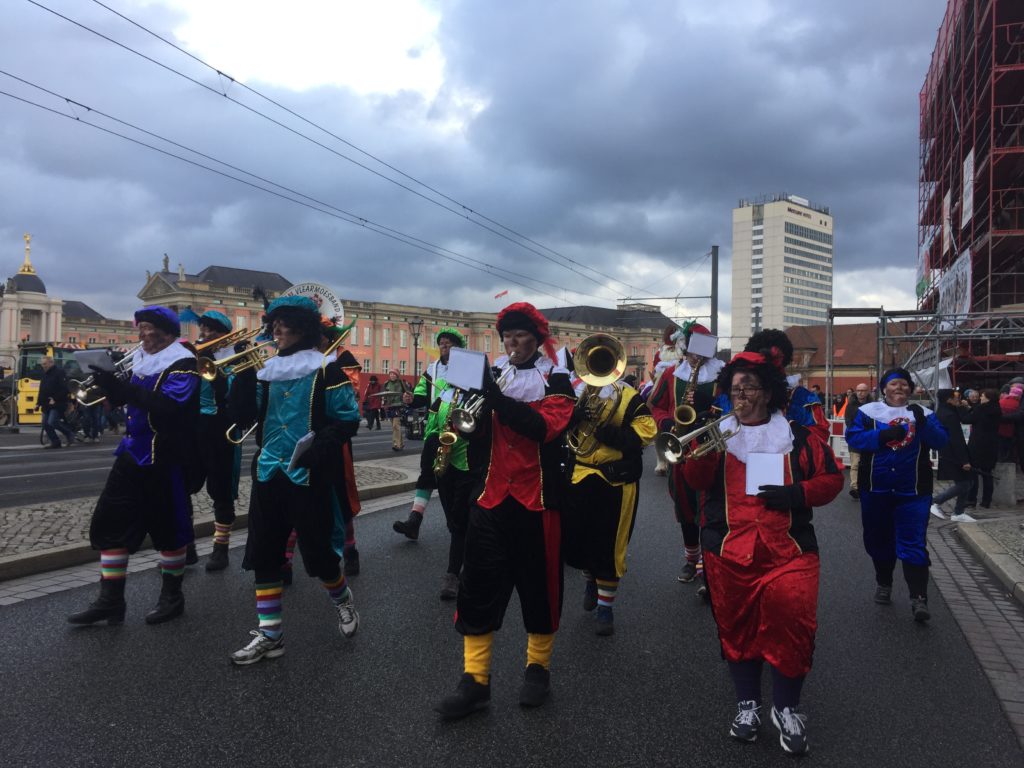

JdA: In the Netherlands we celebrate a children’s tradition called Sinterklaas (St Nicholas in English, French and German). He is an old white man, accompanied by his helper called Zwarte Piet (Black Pete). Zwarte Piet is played by a white person who puts on blackface, wears an Afro wig and also puts on red lips and big golden earrings. If you look into the history of colonial imagery, this is basically recognized as blackface, a type of performance where a non-Black person plays the role of a Black person in a degrading way. The Black character is always dumb, foolish and lazy. This basically perpetuates colonial stereotypes. The tradition of Zwarte Piet tells us a lot about colonial imagery and Dutch history, especially considering that the Netherlands played a big role in the history of slavery and colonialism. But this history is still often silenced in our society.

PP: Is this tradition visible elsewhere than in the Netherlands?

JdA: Sinterklaas is a Dutch import, which means that everywhere where Dutch people are, there will probably be this kind of festivity. For instance in Potsdam, there was a Dutch community and there is a Dutch quarter. This is the reason why they celebrate it there. We do hope that the demonstrations against Zwarte Piet will both spark a discussion about the history colonialism, slavery and institutional racism in the Netherlands, and show that the legacy of this history is global. Dutch people went and still go abroad, some living outside the borders of their country. They often take this tradition with them. Therefore, it should also be addressed there.

PP: How long have you been in the movement against Zwarte Piet?

JdA: The history of the anti-Black Pete movement is a history by itself. One of the biggest misconceptions is that people think that present-day protests against Zwarte Piet are new. This is not true. People have been protesting since the 1980s and 90s. If you look into historical archives, even in the 1950s in the Netherlands, people already questioned Blackface and the character of Zwarte Piet. I started participating in the movement in 2014, three years after a famous protest which inspired me. In 2011, Qunisy Gario and Jerry Afriyie showed up at the national parade wearing t-shirts which said: “Zwarte Piet is Racisme”. They got brutally arrested for that. This violent police intervention obviously upset many people. It also showed how we could not talk about race and racism in the Netherlands. After that, from 2012 to 2014, there were national debates and discussions. In 2014 we decided to found the action group “Kick Out Zwarte Piet” (KOZP) which is a coalition of four Black-led organisations: Zwarte Piet Niet, Stop Blackface, Nederland Wordt Beter and Zwarte Piet is Racisme. We use the symbol to address greater issues, such as institutional racism in the Netherlands. The protest wants to encourage a public debate and demands a greater attention to inequalities in Dutch society, especially looking at discrimination and racial inequality in human and citizen rights.

PP: Has the reception to the protests evolved since 2011? Is your message recognized today by white Dutch society?

JdA: In the beginning, there was a huge backlash. White Dutch people didn’t consider the tradition as racist. A lot of them thought that Zwarte Piet got black because he traveled through the chimney. To them, this explained why he got soot on his face. However, when you look into the colonial archive, you find out that this figure appears for the first time in literature, in a children’s book (in 1850). In the book, he is a Black person, working as a servant and grateful for being a servant to this white old man. This public debate should not be about a children’s tradition; it should address the legacy of colonialism. To go back to your question, the idea that Zwarte Piet is only an innocent children’s tradition is deeply rooted in Dutch society. It is not only widespread among right-wing politicians, but also in the left wing. This can be quite dangerous because then, where do you look for allies? Five years ago and earlier, you would see mostly Black activists and only a marginal amount of white activists who joined the protests. Society was split into Black vs. white with a grey area in between. Thanks to the work of Black activists, people got a little bit more informed and many recognised the emotional value of this sensitive issue. Over the years, that grey area became greyer, darker, which is a good thing. In 2018 and especially last year in 2019, I saw a lot more white activists. This makes me proud. They have indeed access to areas of the population where they can talk about this issue, talk about their stories. Hopefully this can be a turning point. Nowadays, after years of protests and advocacy, there are also more and more social critics who do research and write critical articles, not only about Dutch cultural traditions, but also about human rights violations during the protest. Zwarte Piet is changing at the moment. But the solution that many bring forth is to have so-called “Soot Petes”, not completely black but with stains of soot on their faces. I call it the “blackface-light”. It is still an excuse to keep a blackface performance.

PP: Since 2016 in Potsdam, the local organisation for the “Preservation of Dutch Culture” and their Dutch partners have opted for these “Soot Petes”. The Sinterklaas festivity still takes places and images of blackface can still be seen, for instance on decorative garlands. If the suggestion for “Soot Petes” is still an excuse, as you said, what would be your recommendation?

JdA: I don’t know the particular context of Potsdam, but let me tell you that I don’t believe in the reinvention of the tradition of Sinterklaas and Zwarte Piet. I think it should be completely abolished. This is a thing that I don’t want to be reminded of, as long as the impact of slavery and colonialism can be felt. We should talk about that in the first place. I have no interest in being remembered of this violent colonial history through this figure. Let us once and for all sit down and talk about anti-Black violence, human rights, and re-humanising our society.

PP: Recently, white nationalists have regained power and influence in Europe and in the US. Do your see this evolution in the response to your protests?

JdA: In 2018, we decided to take down 18 cities at the same time, so we needed a lot more people. A lot of white Dutch people joined our demonstration. On the internet, there is footage of a protest in Eindhoven where white women were attacked by nationalists and called traitors. You can also easily find images of Jerry Afriyie, one of the pioneers of the movement, being assaulted by people throwing eggs. There were so many angry white men attacking small groups of activists. It has become very violent. It seems that over the years, the more the story of Zwarte Piet tells its truth, and the more we speak about the impact of slavery and colonialism, then the more angry nationalists and right-wing people get and the more violent the protest become. People do not only get hurt physically, but emotionally and psychologically.

PP: Museums and cultural institutions have started addressing colonial history and its legacies. Do you think that this will contribute to a broader acknowledgment of this past and combat racism in Europe?

JdA: It’s a tough question. I’m not that optimist. The protests between 2011 and 2014 were echoed in the papers and other media and reached the 8 o’clock news. They were also discussed in museums and even within the police, with debates on racial profiling. Since then, the sector of Arts & Culture has really taken on the issue of the legacy of Dutch colonialism. In the last two years, 3 or 4 national museums announced that they would organise exhibitions on the history of Dutch colonialism and slavery (for example Afterlives of Slavery at the Tropenmuseum). This is very good. I think artists and the Arts & Culture sector are always on the foreground when having these debates. They make it a broader discussion. Yet, already in the 1990s in the Netherlands, we saw early waves in the cultural sector that dealt with the issue of racism in cultural tradition. But with hindsight, we’ve seen that it somehow numbed down the discussion. I fear that as we still enjoy this type of art and cultural productions, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the issue of human rights is deeply tackled. This takes time and genuine effort. I’m also a curator, I organise exhibitions, but I still make a very deep distinction between the field of arts and the institutional level. I wish there was some investment in education geared towards addressing institutional racism. Racism does not only take place in cultural tradition; it is a topic for all government ministries. This is a broad political issue. The rights of Black people and People of Color should not be violated anymore. Our lower social and economic position means that there are still strong inequalities in income, and deep consequences in terms of mental health and social marginalisation.