The New Palace and the Peak of the Kilimanjaro

The New Palace is the last building built in the Sanssouci Park. Its construction started in 1769. It’s considered to be the last Prussian baroque palace, built during the reign of Friedrich the Great. It was built as a symbol of his power. The King used it as a reception venue for important dignitaries. A century later, the German Kaiser Wilhelm II renovated the New Palace and made it his favorite residence until 1918.

Inside, there is a massive reception room called the Grotto Hall. Look at the picture of the room: hundreds of colorful stones and shells decorate the walls and ceiling. Among those rocks, one is particularly interesting to us. Sitting on a miniature mountain, a lava rock is described as being the peak of the Kilimanjaro.

To understand how the stone came to Potsdam, we need to go back in time. In November 1884, representatives of European powers gathered in Berlin for the so-called Congo Conference. During three months of debates, they divided the African continent among themselves, like a cake, without any representative from any African community. Germany had laid claim on four regions: Togo, Cameroon, Southwest Africa and East-Africa. A map of German East Africa shows you a territory that encompassed what is now Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi. In the northern region of the colony, a station was erected in Moshi, on the flanks of the Kilimanjaro mountain. This was the home of the Chaga people.

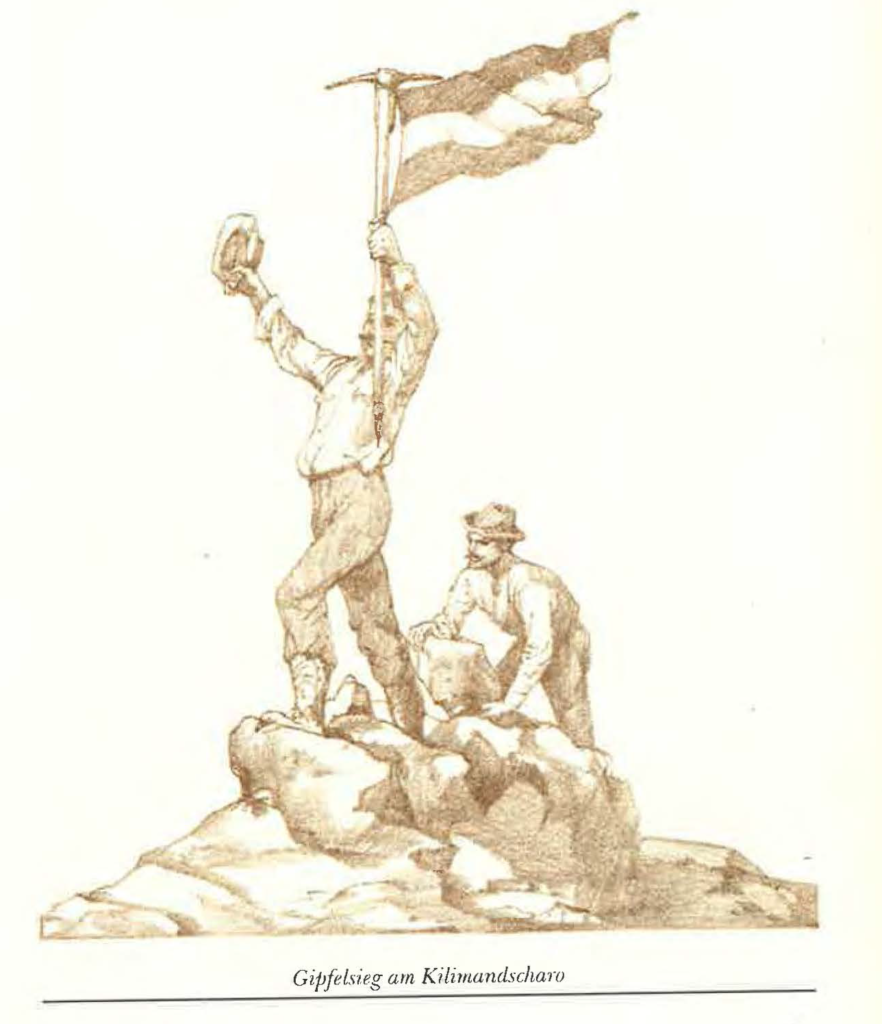

It was there that geographer Hans Meyer started his expedition to climb up the mountain. He was eager to become the first European to reach the top of the highest mountain on the African continent. On 6th October 1889, the expedition reached the summit. A drawing from his autobiography shows Hans Meyer planting the German imperial flag. Although the highest point was already called Kibo by Chaga people, Meyer re-appropriated it and named it “Kaiser-Wilhelm-Peak”. This symbolic gesture would confirm German colonial rule over East Africa in history books.

Obviously, Meyer did not climb up alone. In fact, he would never have been successful without the help of his expedition members. Among them, the Pangani carrier and cook Muini Amani, the Austrian explorer Ludwig Purtscheller, and three Somali carriers. When they reached the second summit – called Mawenzi – Meyer credited it to his European fellow and renamed it “Purtscheller’s Peak”. Africans were not seen by Meyer as deserving mountains with their names. They were enrolled as carriers, just like today in the Tanzanian tourist industry. They were paid a meagre salary for carrying equipment, fetching water, pitching camp, cooking and keeping watch.

After his success, Hans Meyer sailed back to Germany and was received in person by the German Emperor. Meyer offered him half of a lava rock he had collected on top of the mountain: a token from Kaiser-Wilhelm-Peak for the Kaiser himself. It is this rock which would end up being part of the decoration in the Grotto Hall of the New Palace in Potsdam. The other half of the rock was kept by Meyer. We also have a picture of it from an exhibition catalogue. In the 1980s, researchers had the rock in the Grotto Hall tested. They discovered that the original had been replaced by a fake one. This meant that the rock that Meyer gave to the Kaiser had been lost or stolen at some point. The Foundation was offered a replacement stone from Hans Meyer’s collection at the Berlin Central Institute of Geology. But this rock is not from the top of the Kibo. Germany still holds cultural objects, precious stones, fossils and artworks that were stolen and taken away during the colonial era. The restitution of African heritage has been a hot topic in the last decade.

At the end of the First World War, Germany had to surrender its colonial territories. German East Africa was split between a British mandate over Tanzania and a Belgian mandate over Rwanda and Burundi. The name “Kaiser-Wilhelm-Peak” remained in schoolbooks until the independence of Tanzania in 1961. As part of the decolonization process, the summit was renamed Uhuru Peak. “Uhuru” means “freedom” in Kiswahili, the official language of Tanzania.

Learn more on this topic by reading the reactions of Kenyan scholar Oduor Obura and Tanzanian activist Mnyaka Sururu Mboro.