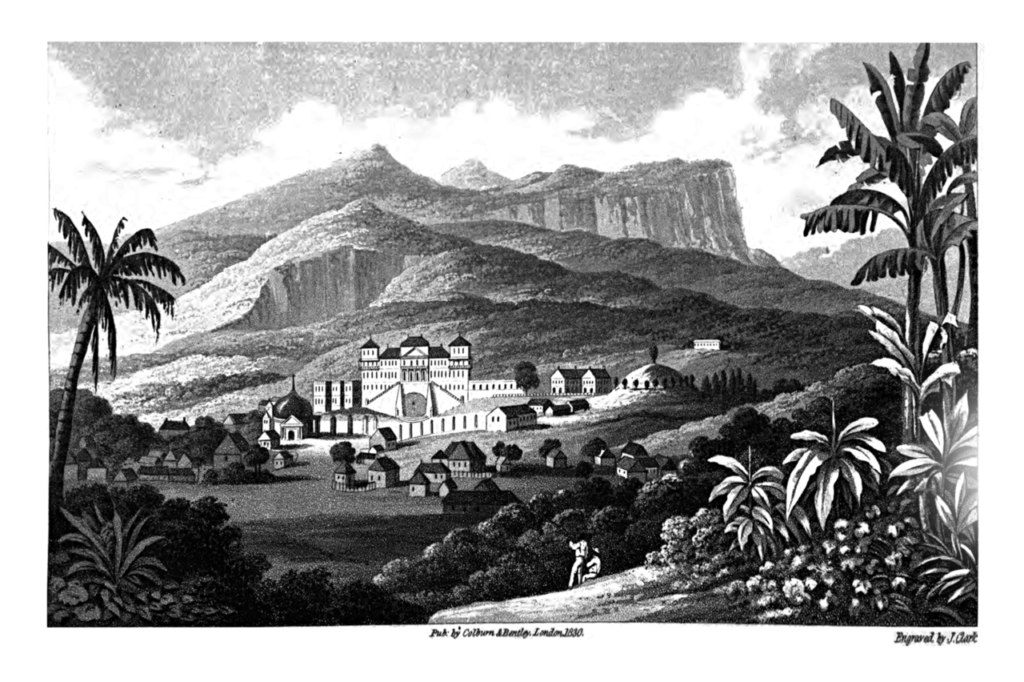

Sans-Souci in Milot, Haiti

This is a translation from a guest contribution by Fabienne Imlinger

It is 1813 in Haiti. In the last years, King Henry I, a fan of architecture, has personally supervised the construction. But his Sans-Souci is more than just an lavish residence for the King. It is a monument for the nation of Haiti, a nation who has just released herself from the shackles of slavery and colonialism.

Ten years have passed since the victory over the French and their colonial rule. The independence of Haiti was proclaimed symbolically on 1st January 1804. But since then, none of the European powers have officially recognized the young state. This is the era of colonial expansion and the Europeans fear that Haiti’s independence might inspire other colonized nations. For these reasons, Haiti remains geopolitically isolated. Besides, the threat of a renewed colonial invasion has not disappeared and France has not given up its claim over their former colony.

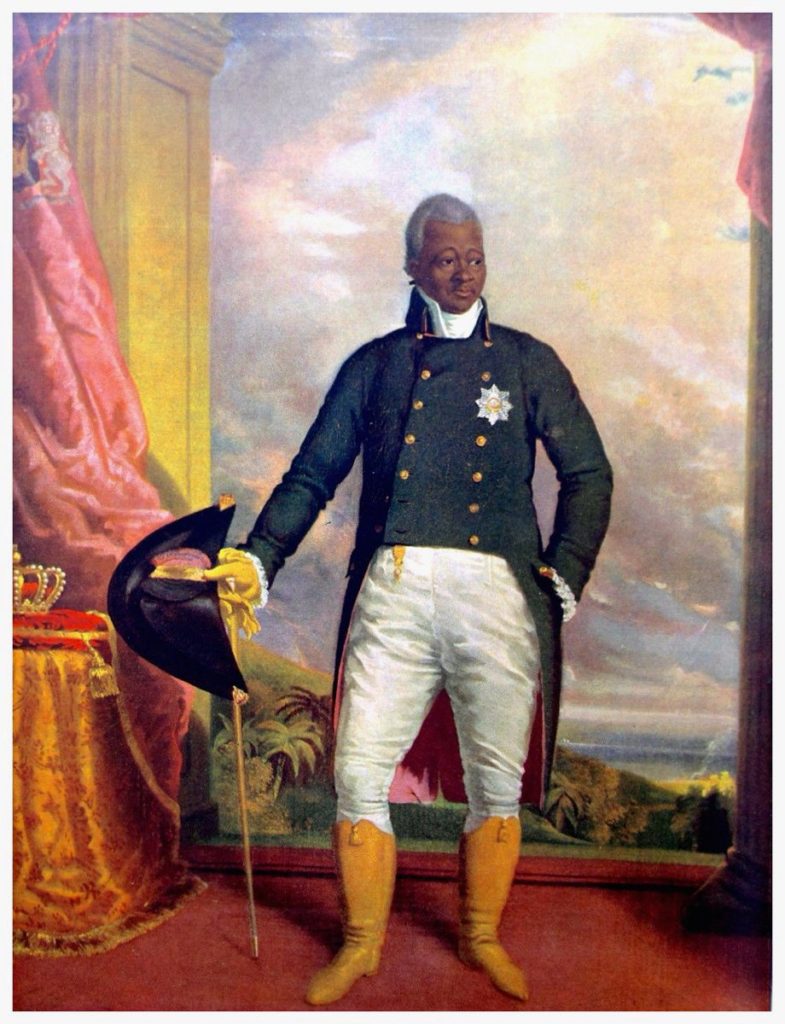

Political conflicts have also taken place within the country itself since the revolution of the enslaved in 1791. The legacy of colonial rule weighs upon the young independent state. In 1807, the specter of civil war could only be avoided by a separation of the territory. Since then, General Henry Christophe rules over the northern part of the island. Like all former revolutionaries, he wants Haiti to become a wonderful nation. He opts for the prestige of a monarchy and crowns himself as King Henry I in 1811. The splendor of royal symbols, institutions and buildings shall shape the image of Haiti’s power, abroad but also at home.

Henry chooses a place near the plantation town of Milot to build his palace and the Lafferière citadel. The two monumental structures form a cluster of royal dwellings. In 1813, Henry, his family and his court settle down in Sans-Souci.

Visitors and writers then started calling this baroque castle a jungle version of Versailles, Schönbrunn or Potsdam Sanssouci. The comparison with Potsdam was evidently suggested by the name. However, historical archives disprove the assumption that Henry chose to name his castle after the one in Potsdam. The connection first appears way later in travel literature from the 1820s and 50s. Henry I and Frederick II are put next to each other, yet mostly with the intention to vilify Henry. Yet, noone questions the unfounded belief that the Milot Sans-Souci is inspired from the Potsdam Sanssouci.

In the eyes of most Europeans, it can only be a copy of a European model. The Eurocentric gaze is blind to the originality of Henry’s palace. But Haiti is already home to a specific type of architecture that differs from European tradition. This is visible for instance in the dome of the palace. The combination of diverse types of masonry, which demands a lot of technical knowledge, is also unusual. The achievements of Haitian architects and workers remain nonetheless invisible to European eyes.

This also bears material consequences. While Frederick’s castle stands right before you, splendid and complete, there are only ruins left from Henry’s palace today. Shortly after Henry died in Sans-Souci in October 1820, the palace was plundered. In 1841, an earthquake finally brings an end to it and it collapses. But the ruins of Sans-Souci continue to fascinate. The cracked remnants still remind of its former greatness and Henry’s ambitions for power. To become an unchallenged monarch, Henry was indeed ready to leave bodies behind him. The truth of Sans-Souci lies under the tumbling walls of the palace, where former slave and revolutionary Jean-Baptiste Sans-Souci is buried.

Jean Baptiste Sans-Souci was enslaved in the Congo region and brought to Saint-Domingue, the name of the French plantation colony before Haiti’s independence. He was at the forefront of the Haitian revolution and belonged to the leaders of the slaves’ uprising in 1791. In 1803, Sans-Souci fought in the war of independence against the French. He employed tactics of guerilla warfare, like most generals of the Haitian army at the time. His success clearly helped tipping the scales in favour of the revolutionaries. It is no surprise then than he found it hard to be forced to kneel to other leaders, especially since some of them had even supported the French at the beginning of the insurrection. Sans-Souci particularly clashes with one of them: Henry Christophe. To get rid of Jean-Baptiste Sans-Souci, he who would become Henry I lures him in an ambush and kills him.

It is near the crime scene that Henry would build his Sans-Souci palace a few years later. Haitian historian Michel-Ralph Trouillot sees here a symbolic act: Henry names his palace to erase the memory of his former enemy. Trouillot’s argument for this paradoxical form of erasure comes from examples from the African continent. The name of the West African kingdom of Dahomey comes from a similar act of naming by killing.

This is how Trouillot solves the mystery of Sans-Souci, breaking off from the European context to bring a logical explanation rooted in the history of the Haitian revolution. He forces us to ask ourselves: which histories remain, and which ones disappear?

Pingback: Celebrating Haitian Heritage Month - Haitian Christian Outreach