Potsdam's Dutch Quarter, "Black Pete" and racist traditions

This is a guest contribution by Lillian Dam Bracia.

Located in the heart of the city, the ‘Dutch Quarter’ is no bigger than four house blocks. It is often also called ‘Little Amsterdam’. This picturesque neighborhood is home to the largest closed Dutch-style buildings outside the Netherlands. The facades of terraced houses consist entirely of red Dutch brick with white joints. It was built between 1733 and 1742 by Dutch architect, Jan Boumann, under the rule of Prussian King Frederick William I and his son, Frederick II. This quarter was supposed to attract skilled workers from the Netherlands.

Prussia was proud of its friendship with its Dutch counterpart. The city of Potsdam besides associates this period of exchange and affluence with Prussia’s openness to the world and to cultural diversity. However, what is dismissed is another and rather dark history of this time. One shouldn’t forget that when the Dutch quarter was being constructed, the Netherlands had built a powerful colonial empire and were participating in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Although from a first impression one would not expect from these cute houses to retain secrets, the troubling fact is they do. They hold secrets tied to slavery, colonialism and racism.

The ‘Dutch Quarter’ celebrates the history of Dutch immigrants and Dutch cultural traditions like Saint Nicolas. However, have you ever heard about the lives and traditions of Africans, Turks and Tartars who also lived in Potsdam and served at Prussian courts in the 18th century? Or about the enslaved people bought off the African Gold Coast or from the Netherlands, forced to work as servants to white noble families?

Along with this hidden history of bondage and enslavement came racist representations of Africans that are visible in traditional Dutch celebrations in the Netherlands, Belgium, but also in Potsdam. Every year, a large audience including families and children come to this part of the city to enjoy the Dutch Christmas market and witness the festivity of Saint Nicolas, known in the Dutch language as ‘Sinterklaas’. Sinterklaas is a white, long-bearded-man who looks like Santa Claus. Every year, he moors at the harbor, rides across the city of Potsdam on top of a horse until he reaches his final destination: the ‘Dutch Quarter’.

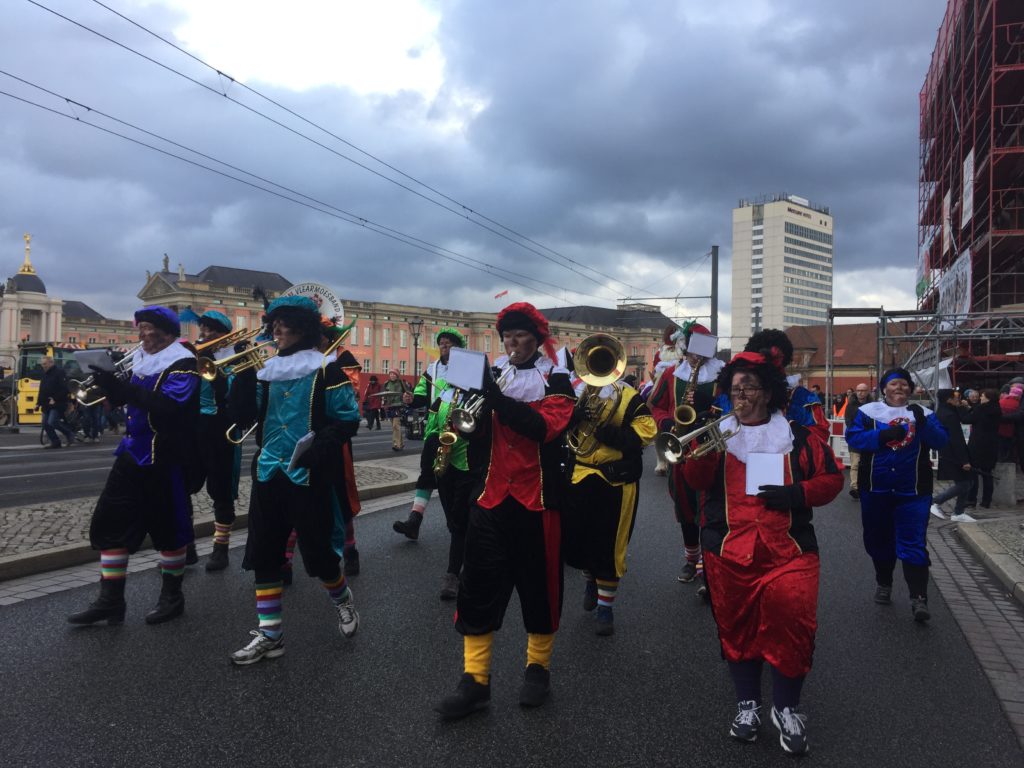

But Sinterklaas doesn’t come alone. He is accompanied by a group of trumpeting and drumming figures walking around him. These are the Petes. More often called Black Pete, it is a contested and controversial figure. He is supposed to be a black man serving and helping Saint Nicolas. But to act as Black Pete, white people put on black make-up, paint their lips red, put on golden earrings and a curly Afro-wig with a feathered hat and a colorful Renaissance costume. This practice is known as blackface. Dressed up, white men and women parade around the streets playing music, cracking jokes, juggling and jumping for the pleasure of a mostly white audience and their children.

The character of Black Pete first appeared in 1850 as an obedient servant to Sinterklaas, thirteen years before the abolition of slavery in the Dutch empire. It comes from a children’s illustration book by a school teacher called Jan Schenkman. In her research on the topic, Afro-Surinamese Dutch cultural anthropologist Gloria Wekker argues that the images of Black people in the book must have influenced the representations of Black Pete in both his character and way of being. He is childish, light and turbulent; funny but a little stupid. He always laughs and wants have fun, in contrast to his wise, serious and benevolent white master Sinterklaas. This contrast has fueled racist ideas on a hierarchy between whites and people of colour. Blackface was actually practiced elsewhere than in the Netherlands. In Great Britain, Germany, Belgium and more famously in the United States, many white performers put on blackface to degrade Africans and people of colour. Until today, this representation has dehumanized Blacks to justify and support unequal power relations. It is tied with the history of European colonial domination and lives on in racist discourse today.

Many people cling to the figure of Black Pete. They argue that it’s a children’s tradition and defend it. They do not see it as a racist practice and claim that Black Pete is innocent and harmless. However, the effects of such representations are not merely symbolic but real, especially for those experiencing racism on a daily basis. Stereotypes are not innocent depictions but actually influence the lives of People of Color and other groups at many levels, not just historically, but socially. Children for instance identify themselves and others with certain characters. In the Netherlands, Black children may be poked fun at or even bullied when they get associated with Black Petes.

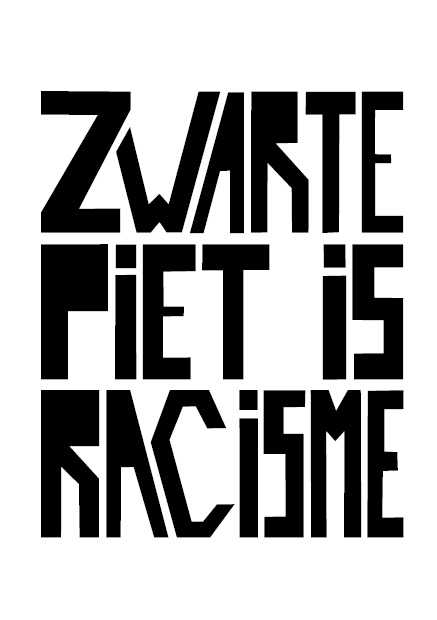

Racism is the construction of difference by defining a body type that represents the norm. It has influenced society for centuries, not only giving white people privilege on the job market, but also creating long-term economic inequalities and positions of power. This extends to the writing of history and the rights to define oneself and define others. In regions where being white is perceived and treated as the norm, representations such as Black Pete remind more of difference and hierarchy than brotherhood and equality. They support theories on racial hierarchy. And they do not provide any explanation on why People of Color have suffered from such theories and why a lot of today’s economic and political inequalities are the result of colonial dynamics, including cultural traditions.

For a truly just and diverse multicultural society, all voices have to be taken seriously. Looking away from historical context and resisting against change in traditions such as Sinterklaas is a form of ‘entitlement racism’. Because it does not affect them, white Europeans allow themselves to distort or ignore the perspective of people affected. Due to constant pressure coming from grassroots and political organizations in the last years efforts have been made to change the tradition of Sinterklaas in Potsdam, with Petes no longer wearing blackface. They are now ‘Soot Petes’ with chimney soot on their faces.