The Orangerie Castle in Potsdam, the Boxer movement in China and astronomical instruments

Between 1901 and 1919, Chinese astronomical instruments decorated the patio in front of the Orangerie in Potsdam. Germany had to give them back to China as part of the reparations for the First World War. These instruments had been looted by the German military during a period of German colonial occupation in China. This conflict is known in English as the Boxer War or 義和團運動. (Yi He Tuan yun dong)

Since 1882, Catholic missionaries had settled in the Shandong province with the aim to proselytize the population. At that time, the German Empire was eager to acquire a naval base on Chinese shores. Britain had already done this forty years earlier with Hong Kong. The German navy was then waiting for an opportunity to annex the Jiaozhou Bay in Shandong. When two German priests were murdered in 1897, Kaiser Wilhelm II used it as a pretext for a military intervention. 600 soldiers landed and occupied the bay. Forcing negotiations upon the Chinese government, Germany obtained a lease agreement of 99 years. From 1898 until the beginning of the First World War, the Kiaotschou Bay concession was then under German occupation. Germany wished to build a model colony there. The government invested in infrastructure to develop the administrative centre of the colony, the city of Qingdao. They paved the town with wide streets, built houses and institutions, spread access to electricity and developed a sewer system. Schools were funded by the Berlin treasury and the missionaries.

Yet this only benefited German settlers. The Chinese population was relocated and therefore rose against this foreign oppression. The German military brutally crushed the first revolts. As resentment against violent occupation in Jiazhou and elsewhere grew, an anti-foreign movement was born. They called themselves “Yi He Tuan”, which means “Martial art fighters united in harmony”. Europeans called this secret society “The Boxers” because they knew little about the Gong Fu fighting style. In several occupied territories along the coast, the so-called Boxers attacked French, Italian, German and British missionaries and soldiers. In their slogans, the movement recognized the imperial Qing dynasty as their sovereign rulers.

In Beijing, Chinese Empress Dowager Cixi decided to support their struggle officially. She sent her army to push foreign troops to withdraw. As a reaction, foreign governments who had claimed territories in the northeast agreed to form the “Eight Nations Alliance”. With troops from Japan, the United Kingdom, Russia, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy and the U.S. the Alliance were initially turned back by the Chinese. But when European governments sent 20,000 soldiers as backup, the Chinese had to retreat. Beijing was under siege and sacked in late summer 1901. Russian, Japanese and German soldiers plundered the capital. The Potsdam-born general Alfred von Waldersee sent punitive expeditions to the surrounding countryside to execute those suspected of being Boxers. In reality, the soldiers massacred thousands of civilians. As one of the architects of this brutality, Waldersee also settled in Dowager Cixi’s headquarters when German troops conquered the imperial city. This added a taste of humiliation to China’s defeat.

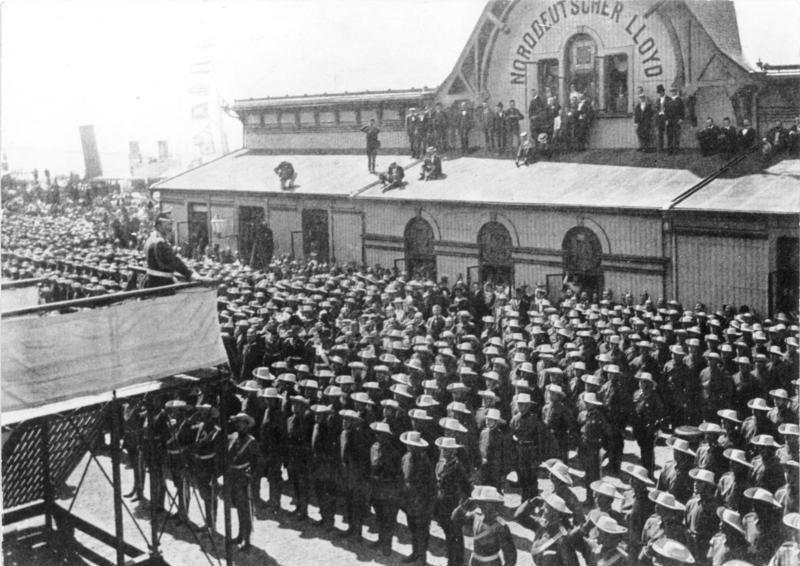

The German Kaiser himself had paved the way for such violence to happen. In 1900 he addressed soldiers embarking for China with the following words:

“Should you encounter the enemy, he will be defeated! No quarter will be given! Prisoners will not be taken! Let all who fall into your hands be at your mercy. Just as the Huns a thousand years ago under the leadership of Attila gained a reputation, so may the name of Germany become known in such a manner in China”.

This unrestrained speech went down in history. Since that day, Germans have been called “the Huns” in a derogatory manner.

After the Chinese Imperial family surrendered, the winners defined the post-war agreements. The terms stipulated that government officials who had supported the Boxers should be executed. On top of that, 450 million taels of silver – approximately $10 billion – should be paid as indemnity by China to the eight nations. The German Kaiser demanded that a Chinese delegation express formal apologies in person. Zaifeng II, a.k.a. Prince Chun, was forced to travel to Potsdam. An official ceremony took place here on 4th September 1901, in the Grotto Hall of the New Palace. To avoid full humiliation, the prince refused to kneel in front of the Kaiser.

As part of the plunder of Beijing, astronomical instruments from the city’s observatory were shipped to Potsdam. After Germany’s defeat in the First World War, China asked for these instruments to be returned. A clause for their restitution was integrated to the Versailles Treaty. Since 1920, they have been on display in front of the Beijing observatory.

German colonial presence in China has left more visible traces than the absence of those instruments: Tsingtau was not only the name of Qingdao under German rule; a beer brand bears the same name and attests of former German presence in the city when the brewery was first established. In Berlin, not far from the so-called African Quarter, a Kiaotschou-street also reminds of this largely unknown history.